As Seen in TEQ Magazine: Does Failure Breed Success?

The tech world’s mantra, “Fail fast, fail often” is so pervasive that failure is a kind of success in and of itself. Worn like a badge of honor, failure is not only invoked, but downright celebrated. Entrepreneurs give speeches detailing their screw-ups. Academics laud the virtue of making mistakes. FailCon, a conference about embracing failure, was launched in San Francisco five years ago and is now an annual multi-city event with technology hubs in Barcelona and Tokyo.

As digital innovators, the only way to stay relevant is to try new things, knowing that many of those attempts will fail. The lessons I have learned building a software company are many, but by far the biggest is that it is better to fail trying than to not try at all.

Word is, 9 out of 10 startups fail. According to Small Business Association statistics, 69% of new businesses survive 2 years and 51% survive 5 years. The number of VC-funded startups that survive 5 years out is around 1 in 5. These numbers have not changed significantly in the past 20 years. But every once in a while, a winner like Duolingo or ModCloth arises from the dust and becomes revolutionary.

That’s what we hoped would happen with Vivo Live, a hardware-software product we created that connects any camera to any computer, enabling livestreaming between connected devices.

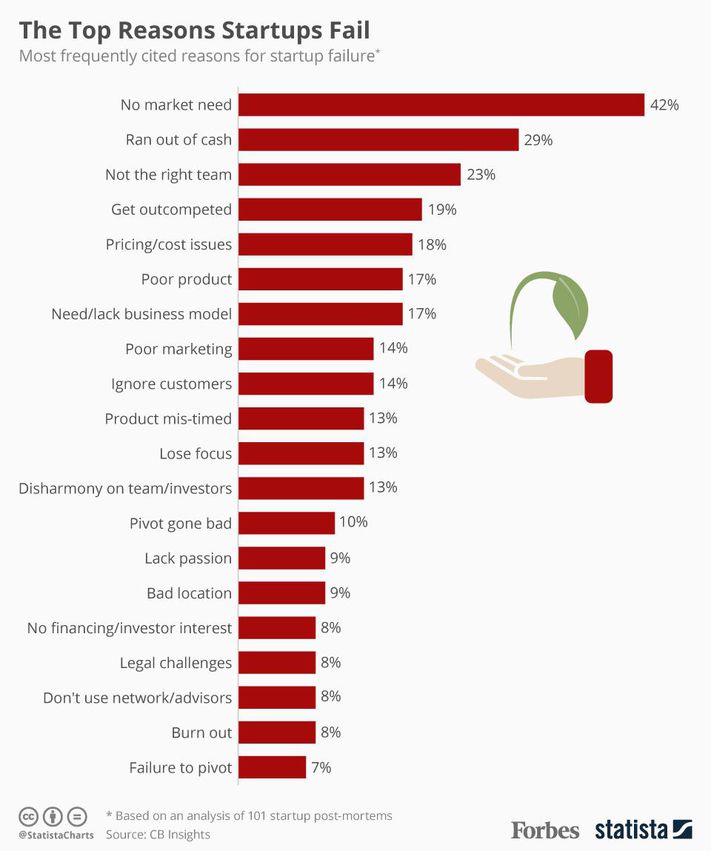

The number one reason startups fail is a lack of market for the product–if people don’t want what you have to sell, better sell something new. In 2009, the year we launched Vivo Live, there was a market of 100 million video viewers online and only 1 million creators publishing live broadcasts. It seemed like the perfect moment for Vivo Live. We got 4 major publishing houses to sign on, created a prototype, partnered with a manufacturer, and sold Best Buy 10,000 units of our hardware, all while pitching angel investors and government funders on future investments.

While it appeared that the ideal market existed for Vivo Live, in reality people were just beginning to watch video online–they weren’t ready to produce or livestream it themselves. In years since, companies like Livestream and Twitch have adopted livestreaming technology to huge success, but Vivo came too soon and without the right market niche.

While the timing wasn’t ultimately right, Vivo’s hardware-software combination also failed. The chip we used in the hardware only worked on older computers, and the system was built on Flash, which led to the eventual demise of the software. After two years, we did not have the resources to evolve our platform, so our co-founders moved on, leaving me the last entrepreneur standing.

In hindsight, Vivo Live was not destined to succeed because of a combination of product shortcomings and–more fundamentally–bad timing. This is true of many innovative ideas: some fail because of bad planning, some fail because there’s no market, but in many cases, they fail because the market hasn’t matured enough to see the need for the product yet. Sometimes excellent marketing can show potential markets the value of the idea, and sometimes it can’t.

Vivo Live taught me the importance of building products that can adapt to new needs. Today, when we build websites and web apps for our clients, we do extensive research on their needs, the needs of their clients, and their market. We create digital solutions that can grow, change, and adapt to shifting goals, more content, and new functionality.

The biggest personal takeaway for me from my experience with Vivo Live is a change of mindset. I used to consider myself a digital marketing professional, but now I take pride in being an innovator. Vivo Live taught me about entrepreneurship, and I have become a bigger promoter of taking measured risks in the years since. I will continue to launch quickly and launch often, knowing that while many innovations fail, success means trying anyway.

Fort Ligonier Days: 60th Anniversary

Fort Ligonier Days: 60th Anniversary  JCC PGH: Center for Loving Kindness

JCC PGH: Center for Loving Kindness  Wagner Agency

Wagner Agency  OBID: You Are Here

OBID: You Are Here  Breathe Project

Breathe Project

Be the first to comment!